Our debt ceiling issue has been alleviated(!) … for now.

As suspected, at the last minute, Congress reached a final agreement on June 1st to avoid the global drama that would come from a sovereign downgrade.

The main takeaways from the deal, at least for me, were:

- Student loan payments will be back toward the end of the summer. Millions of people will go back to paying $200-300/month in student loan payments toward the end of the summer.

- They will claw back about $28 billion of unused Covid relief funds. Extracting more dollars from being poured back into the economy.

- And most importantly, technically, they only “suspended” the debt ceiling. Essentially allowing the Treasury to supersede the limit for a period of time. Taking the threat of a default of the table until 2025.

The debt ceiling conversation is an ever-so-reoccurring one. So with that said, in a few years, Congress will need to explore additional methods to increase tax revenue or risk diving deeper and deeper into the red. “Biden said … he is willing to cut spending, but added that we have to also look at the tax revenues,” Erin Doherty at Axios wrote.

One of those methods could be the “death tax.”

More specifically, the taxes on wealthy people’s estates at death which resulted in a measly $33B in tax revenue last year.

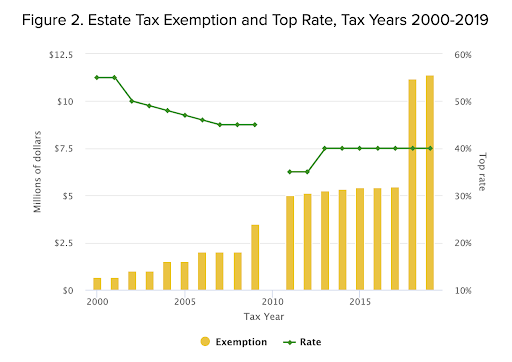

I’m sure Congress will have its eyes on this when the next debt ceiling circus is back in town. Coincidently, ending in December of that same year is the Federal Estate Tax Exemption limit, which is currently $12.92M. And it’s worth mentioning, around this same time the current administration is leaving the White House, putting Congress in a lame-duck session.

To most of us, the response is OK… And?

Well, why this may be relevant to you is that, in just a few years, this number is set to sunset back to 2017 levels — $5.5M. Some are estimating it to be $6.7M after adjusting for inflation.

This means many more regular people, like your parents or grandparents or maybe even you, who aren’t uber—nvidiawealthy but will have enough assets to creep against that large number, may be affected at some point.

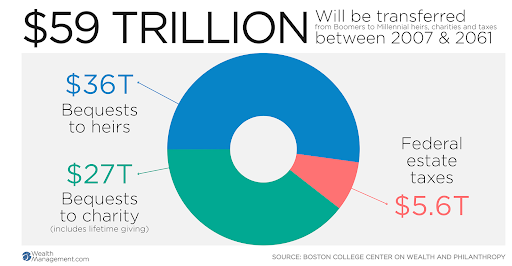

Failing to act now could eat away at future inheritances and be a key headwind in the Great Wealth Transfer.

So what even is the estate tax exemption limit and this “death tax?”

Below I’ll answer why it’s important to plan for this tweak in the tax code, and the solutions the wealthy are using today to shield as much of their assets from this tax as possible and pass on the maximum amount to those they care about.

Some Background on the Federal Exemption Limit

As a quick primer, the “death tax” is a variety of taxes owed on the value of the assets individuals leave to their heirs or inheritors pay on assets and property received. Most notable is the federal and state estate taxes.

An estate tax is a tax levied on the value of an estate at the time of the deceased’s passing.

The federal exemption limit is the amount subtracted from your gross estate when calculating whether you’ll have an estate tax liability or not. Generally speaking, as long as your total gross estate (adding up all your assets plus any taxable gifts) doesn’t exceed $12.9M, (doubled for married couples) you won’t have a federal estate tax problem. Although, each state is different. So, you’ll have to check your particular state’s laws to find out what their limit is.

I’m not going to give you the entire history of the estate tax. Given you probably don’t want to know, and because a lot has changed since its inception in 1916.

Although many of the structural clauses that we still use today — like the unlimited marital deduction and the annual gift tax exclusion — originated before 1976, our modern structure starts from there on out.

The exemption amount was set to a cool $1 million dollars in 2002, and the ceiling gradually rose over several years until 2010. Where interestingly enough, there was a tweak in the code that repealed the federal estate tax until it was brought back in 2011 and became a permanent part of the tax code in 2012.

In all, this tax isn’t something most people spend their day worrying about.

Although less than 1% of estates have historically ever been affected by this tax, it wasn’t until the TCJA of 2018 that it really left people’s minds when the limit doubled to $11M.

For example, only about 2,500 estates were taxable in 2021 out of the 6,100 estate tax forms that were filed. Compared to the two decades before when nearly 52,000 taxable estates were filed in 2001.

Because the exemption limit has been set so high, much of estate planning work has shifted its focus from estate tax minimization to income tax minimization in recent years.

I have a sneaking suspicion that the 2025 debt ceiling showdown and 2026 expiration date could change this.

Why It’s In Question Now: The Debt Ceiling Crisis Puts This Back on the Table

The recent debt ceiling crisis has put spending and how we make up for that spending under a microscope.

We’ve heard many times that the current mismatch of this country’s income to liabilities is simply unsustainable. Scott Hodge at the Tax Foundation claims, “many are pointing to tax policy as both the cause of and solution to the debt crisis.”

And estate and inheritance taxes have been a political debate for a long time.

Some argue that the tax dissuades wealth accumulation, slowing a nation’s economic growth. At the same time, the opposition argues that it’s a stable source of tax revenue, encourages successors to work, and it prevents the concentration of wealth from only going to a small pool of families.

And they’ve got a point. The CBO writes, “Estates valued at $50 million or more accounted for 6 percent of all taxable estates in 2018 and held 42 percent of assets reported by taxable estates in that year.” Imagine if there was no limit? Remember 2010?

I wouldn’t necessarily call it a “stable” source of tax revenue either. Counting back from 2017 to 2001, estate tax revenue has declined by 98%.

To help against pushing on the debt ceiling again and fueling the national debt, congress will start to look at creative ways to collect more tax dollars. For example, taxing corporate stock buybacks, eliminating certain tax breaks, or a more progressive consumption tax is either here or feasible. Therefore, I see no real push to fight this ugly sunset and keep the limit heightened.

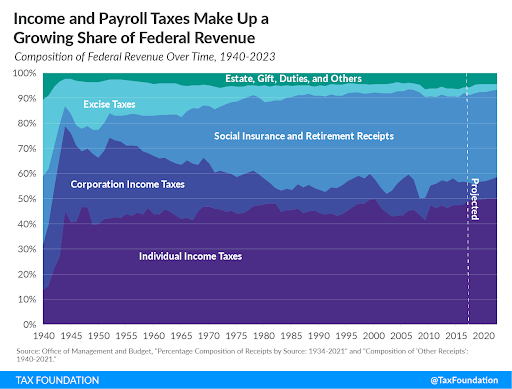

In 2022, estate and gift taxes made up less than 1% of the Federal tax revenue and just 0.6% in 2014. So, historically, it has never been a significant share of the revenue pie anyway. Still, every little bit helps.

It’s very hard to estimate what the ramifications of lowering the exemption amount would be. But given Boomers collectively hold some $78T in assets, it’s safe to assume that fewer affluent families will be able to scathe by under this shortened limit.

Just like it was a wise move to lock in any kind of borrowing rates while the good times lasted, these next few years are a good time to capitalize on this high ceiling.

So how are the wealthy taking advantage of the ~$13M, or $26M for married couples, limit today?

Solution For Regular Millionaires

Just to reiterate, the exemption amount falling back to single-digit million-dollar levels won’t affect many people. But, for those who it will affect, failing to act now could cost inheritors tons of money.

The consensus seems to be that the current level between now and 2026 is on a use-it-or-lose-it basis.

The latest IRS ruling states, “Beginning in 2026, your estate tax threshold will be the greater of the estate tax threshold then in place OR the total taxable gifts you have made during life.”

The number one way they are taking advantage of the multimillion-dollar exemption limit today is actually by giving it away.

Of course, when you have that kind of money, you’ve got options. You could gift it to yourself while still getting the assets out of your total estate. But we’ll save the complexities and nuances of those strategies for another day.

More notably, one of those options is to give it away to someone else who could really use it. Grandkids who still have a long time until college starts. Paying for a house in cash for their own kids. Nieces and nephews who could really use that money today.

But not all agree that’s the best use of the money they spent a lifetime accumulating.

Another option, and what comes to most people’s minds, are charities. Now, you can get fancy by combining the second option and this one by using an expensive charitable trust. Or, you could donate it today. A donor-advised fund takes both cash and low-basis non-cash assets you already deemed to be a tax issue.

Or give it all up after you pass away. I know you’re all dying to do that.