Starting difficult things is much harder than finishing them.

For example, looking at the introduction pages of a thick novel is much more daunting than when you’re halfway through the book.

Day one of your “get back in shape” journey is much harder than week 52 when the incremental progress is much more visible.

We know that. But it’s also fair to say the timing of these actions is equally important because it affects your experience when doing them.

For instance, I purposely schedule my runs and workouts in the morning to start with a fresh mind and body, as opposed to most afternoons, when the day has sapped my mood and energy.

The same goes for making virtually any tough decision, especially when it comes to our money. Choosing the right time to make important financial decisions can significantly impact your outcome.

It’s evident that the day and market environment in which you invest will affect your short-term rate of return and, thus, your experience until you get to bear the fruits of the pain you endured in the beginning.

My colleague, Blair DuQuesnay, calls this kind of advent risk, “inception date roulette.” Your starting point on an investment journey involves an element of randomness that will impact your returns right out of the gate.

When starting your investing journey with a new advisor or getting into a new investment, our attention is typically hyper-focused on the short-term results — much like when you start a Tolstoy novel or start an exercise regimen.

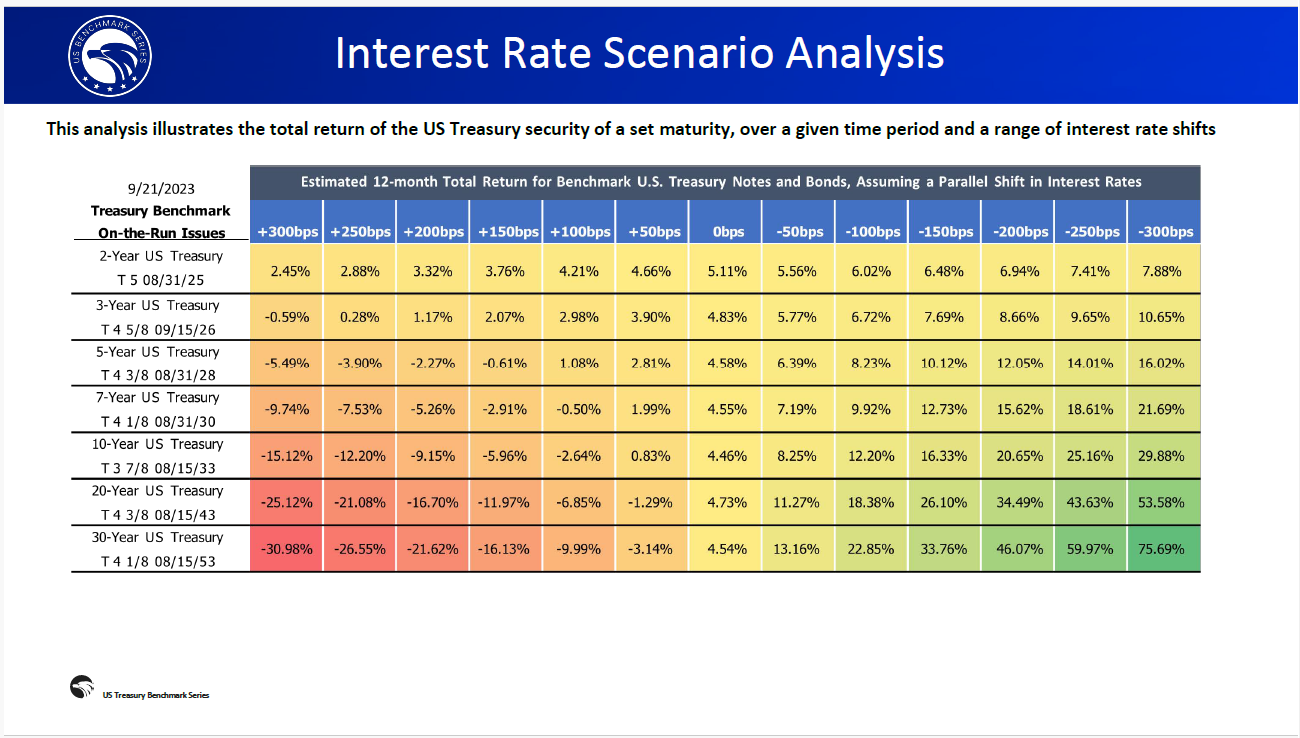

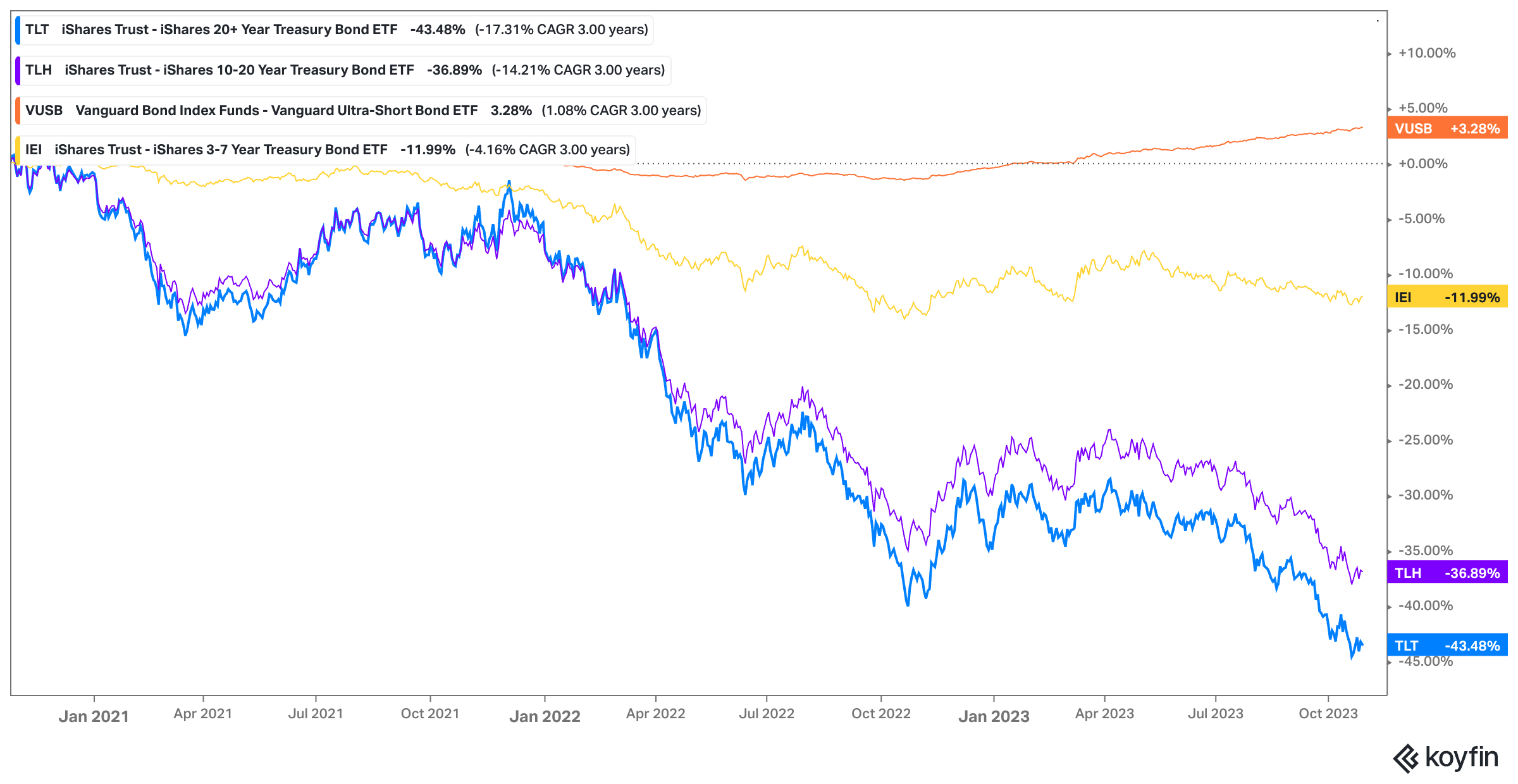

Similarly, many investors now see the risks of investing in bonds for the first time. Depending on where in the yield curve you aim to invest, your investment experience could be wildly different.

It goes to say that timing is crucial in bond investing, especially when considering interest rates and your starting yield.

Longer-dated maturity bonds—10, 20, and 30-year bonds—got crushed as a result of the sharp rise in interest rates. After three years, long-term bond ETFs TLH and TLT still see losses of up to 36% and 43%, respectively. Meanwhile, ultra-short-term bonds, which weren’t paying much of anything before then, fared much better.

Fortunately, the future looks a lot brighter for your bond allocation than it did when rates were near zero.

On this topic, Michael Batnick wrote a few weeks ago, “With yields breaking out to new cycle highs, I’m not brave or dumb enough to say that today is the top, but if the 10-year rises another 100 bps (1%) from here, they will decline ~2.6%. But if it falls 100 bps, they’ll rally 12%. The same shift for 20-year bonds would result in a loss of 6.9% or a gain of 18.4%.”

Still, conventional wisdom today assumes we’re much closer to a peak in rates than we are to substantially higher hikes. And bonds today have something today that we didn’t have in the years prior—a yield to back them up. Therefore, the price volatility you may see going forward could be less critical to your portfolio regardless of where the Fed decides to take rates from here.

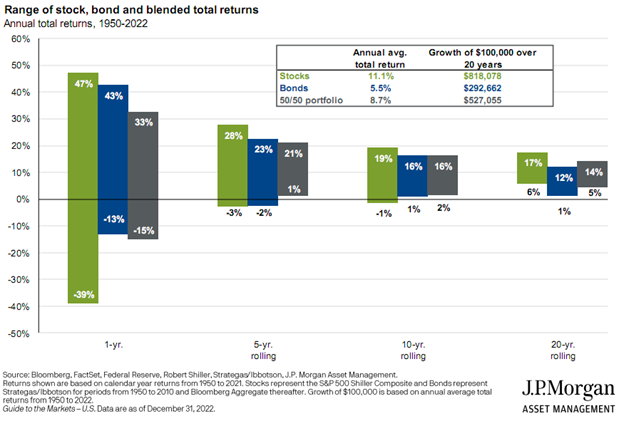

Stocks are no different. Performance results in a given year are a crapshoot.

Going back to 1871, the S&P 500 was down 35%, 28%, and 21% of the time over a 6-month, 1-year, and 2-year period, respectively.

Knowing which stock market regime you will invest in in the short term is impossible. To date, the market is still down by 10% since 2021. Investors who entered the market after the euphoric run-up two years ago may still be in the red.

However, keeping your eyes glued to your return metrics in the first few months or years is a useless and unhealthy use of your time unless you’re day trading.

Your returns typically begin to normalize after staying put for several years. This graph from JP Morgan shows the total return range for stocks and bonds over various periods of time. In one year, returns can vary widely, for better or worse. However, after five years, both asset yields are much more skewed to the upside. And after a rolling 20-year period, your likelihood of seeing a loss is slim to none.

It’s not a secret that one way to really juice your returns is by taking action when markets are off their all-time highs.

Having said that, timing the market is nearly an impossible task to successfully repeat over time.

As Barry Ritholtz wrote a year ago, “the vast majority of Alphas chasers underperform the indices after a few years. After 10 years net of fees, there are practically zero outperformers… We know the names of people like Ron Baron and Peter Lynch and Warren Buffett not because they are typical stock pickers, but because they are the rare outliers.”

Dollar-cost averaging into the market takes the guesswork and the need for precision out of the equation. Additionally, for taxable brokerage accounts, the various lots allow you to cherry-pick long-term lots and take advantage of strategies like tax-loss harvesting to improve your after-tax return.

Although difficult because it seems like that’s all that matters, you can’t always judge an investment in the near term. It takes time.

And that’s what it’s always about: time.

In summation, it’s true. Sticking with the difficult things in life is hard.

Your mind and body can often give you conflicting advice. But it’s important to ratchet your senses back to the end goal. What did I set out to do, and how long am I prepared to do it?

We know that timing the market is a fool’s errand. Knowing when the right or wrong time to invest is like knowing when the right or wrong time is to start a new hobby, like learning an instrument or picking up a sport. Or embracing a healthier lifestyle, like regular exercise or making mindful dietary choices. It’s something you can kick off at any moment.

My colleague met his wife on an off Tuesday at his first real job out of college. If it weren’t for that perfect cosmic mix of circumstances, he would not have two beautiful children to come home to today.

The lesson to be learned is that it’s not so much when you start. It’s that you started.